System developed by MIT, including co-author Mathew Wilson, and Open Ephys team provides a fast, light, standardized means for combining multiple instruments with minimal hindrance of lab mouse mobility.

David Orenstein | The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

November 13, 2024

Individual technologies for recording and controlling neural activity in the brains of research mice have each advanced rapidly but the potential of easily mixing and matching them to conduct more sophisticated experiments, all while enabling the most natural behavior possible, has been difficult to realize. To empower a new generation of neuroscience experiments, engineers and scientists at MIT and the Open Ephys cooperative have developed a new standardized, open-source hardware and software platform. They described the system, called ONIX, in a new study Nov. 11 in Nature Methods.

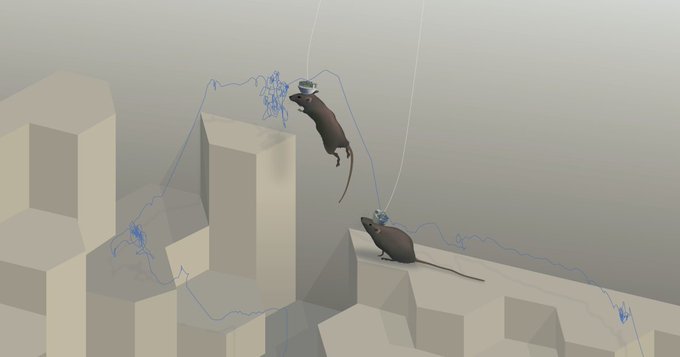

ONIX provides labs with a means to acquire data simultaneously from multiple popular implanted technologies (such as electrodes, microscopes and stimulation probes) while also powering and controlling those independent devices via a very thin coaxial cable and unimposing headstage. The system provides a standardized means of acquiring each instrument’s data and neatly integrating it all for efficient transmission to desktop software where scientists can then see and work with it. In the study the researchers document ONIX’s high data throughput and low latency. They also demonstrate that because the system’s headstage and cable are so physically light and resistant to twisting, mice can behave completely naturally and wear the system for days on end. In a large enclosure at MIT with a complex 3D landscape, for instance, mice wearing the system were able to nimbly scamper, climb and leap in experiments comparably to mice wearing no hardware at all.

“ONIX represents the culmination of many quantitative improvements that all come together to enable a qualitative leap in our ability to perform neural recordings in naturalistic behavior,” said corresponding author Jakob Voigts, an MIT neuroscience alumnus, co-founder of Open Ephys, and a research group leader at the Janelia Research Campus of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. “We can now study the brain during behaviors that unfold over many hours and allow the animals to learn, to make a lot of complex decisions, and to interact with the world in ways that were previously not accessible.”

Jon Newman, a former MIT postdoc and now president of Open Ephys, and MIT postdoc Jie “Jack” Zhang led the work in the lab of co-author Matt Wilson, Sherman Fairchild Professor in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT, together with Aarón Cuevas-López at Open Ephys. Wilson, whose lab studies neural processes underlying memory, said the idea behind developing ONIX was to develop a set of standards that would make it easy for any lab to use multiple technologies to acquire rich neural data while animals performed complex behaviors over long time periods.

“Jon’s motivation, the principle he used, was that if we need to do experiments that combined things like optogenetics, imaging, tetrode electrophysiology, and neuropixels, could we do it in a way that would not only enable experiments we were doing but also more complex experiments, involving more complex behavior, involving the integration of different recording methodologies that advances the whole community and not just one individual lab?,” said Wilson, a faculty member in MIT’s Departments of Biology and Brain and Cognitive Sciences (BCS).

Open origins

As Newman and then Zhang began to develop the technology starting in 2016 with this community-minded, open-source philosophy, Wilson said, it was natural to do so in partnership with Open Ephys, an MIT-born effort, now based in Atlanta, which develops and disseminates open, standardized systems to for neuroscience research. Making systems open-source provides researchers with many advantages, Voigts explained.

“Anyone can download the plans for the hardware as well as the software that make up the system,” Voigts said. “For technically well-versed neuroscientists this means that it is easier to modify aspects of the system. Open source also means that the system works with probes from many manufacturers because the connectors and standards aren’t proprietary. Most importantly, the open standards and design allow hardware and software developers to use ONIX as a starting point for completely new tools.”

Voigts compared ONIX to the USB standard people enjoy on their computers and phones. Any number of accessories can easily work with those devices because all they have to do is plug in. Similarly with ONIX, Wilson said, “You can mix and match and combine and then add new technologies without having to re-engineer the whole system.”

Lab demos

To validate the platform, the researchers conducted several experiments with mice including in Wilson’s lab and in the lab of co-author Mark Harnett, Associate Professor in the McGovern Institute for Brain Research and BCS Department at MIT (where Voigts did his postdoctoral work).

In their experiments they compared the mobility of mice implanted with electrodes but sometimes wearing ONIX (and its 0.3 mm tether cable) vs. sometimes wearing a commonly used and but substantially thicker (1.8 mm) tether cable over an 8-hour neural recording session. The mice proved to be much more mobile while wearing the lighter and thinner ONIX system, showing a broader range of exploration, freer head movement, and much faster running speeds. In a similar experiment in which mice were inplanted with tetrodes in the brain’s retrosplenial cortex, they even were able to jump while wearing ONIX but did not while wearing the more imposing tether. In another experiment the researchers compared mouse mobility around the enclosure between ONIX-wearing and completely unimplanted mice. The mice explored with equal freedom (as measured by motion tracking cameras) though the ONIX mice didn’t run as fast as unimplanted mice.

In further experiments, Voigts’s team at Janelia used ONIX to record for 55 hours because the system kept its cable tangle-free over that long-duration activity.

Finally the researchers showed that ONIX could transmit recordings not only from implanted electrodes and tetrodes but also from miniscopes and neuropixels, via experiments at the Allen Institute for Brain Science. They also showed how Open Ephys’s data acquisition software Bonsai (developed by co-author Goncalo Lopes) enabled the brain activity recordings to be synchronized with behavior tracking cameras to correlate neural activity and behavior.

Voigts said he hopes the system earns widespread adoption, especially as hardware costs continue to come down.

“I hope that this system convinces others to take the plunge and record neural data in more complex animal behaviors,” he said.

In addition to the authors named above, other authors are Nicholas Miller, Takato Honda, Marie-Sophie van der Goes, Alexandra Leighton Felipe Carvalho, Anna Lakunina, and Joshua Siegle, who co-founded Open Ephys with Voigts.

Funding for the study came from the National Institutes of Health, The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, The JPB Foundation, the National Science Foundation, a Brain Science Foundation Research Grant Award, a Kavli-Grass-MBL Fellowship by the Kavli Foundation, the Grass Foundation, and Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), an Osamu Hayaishi Memorial Scholarship for Study Abroad, a Uehara Memorial Foundation Overseas Fellowship, and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Overseas Fellowship. a Mathworks Graduate Fellowship. The Simons Center for the Social Brain at MIT and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.