Biologists demonstrate that HIV-1 capsid acts like a Trojan horse to pass viral cargo across the nuclear pore.

Lillian Eden | Department of Biology

January 24, 2024

Retroviruses cannot replicate on their own — they must insert their genetic code into the DNA of a host and exploit the host cell’s resources to make more copies of themselves, furthering infection. Some retroviruses only infect cells as they divide, when the nuclear envelope that protects the host’s genetic material breaks down, making it easily accessible. HIV-1 is a type of retrovirus, called a lentivirus, that can infect non-dividing cells.

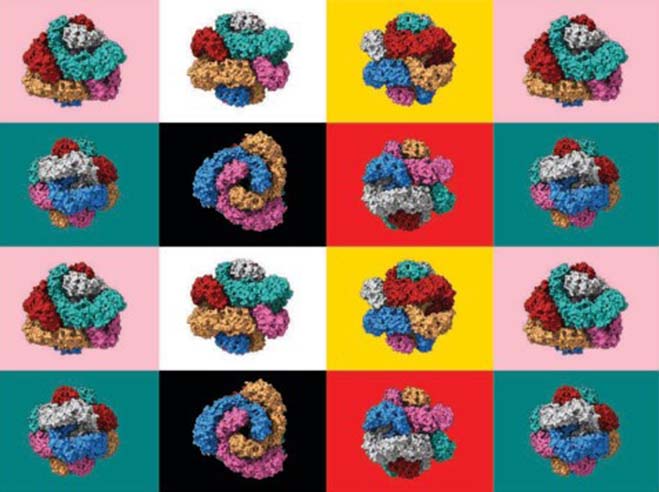

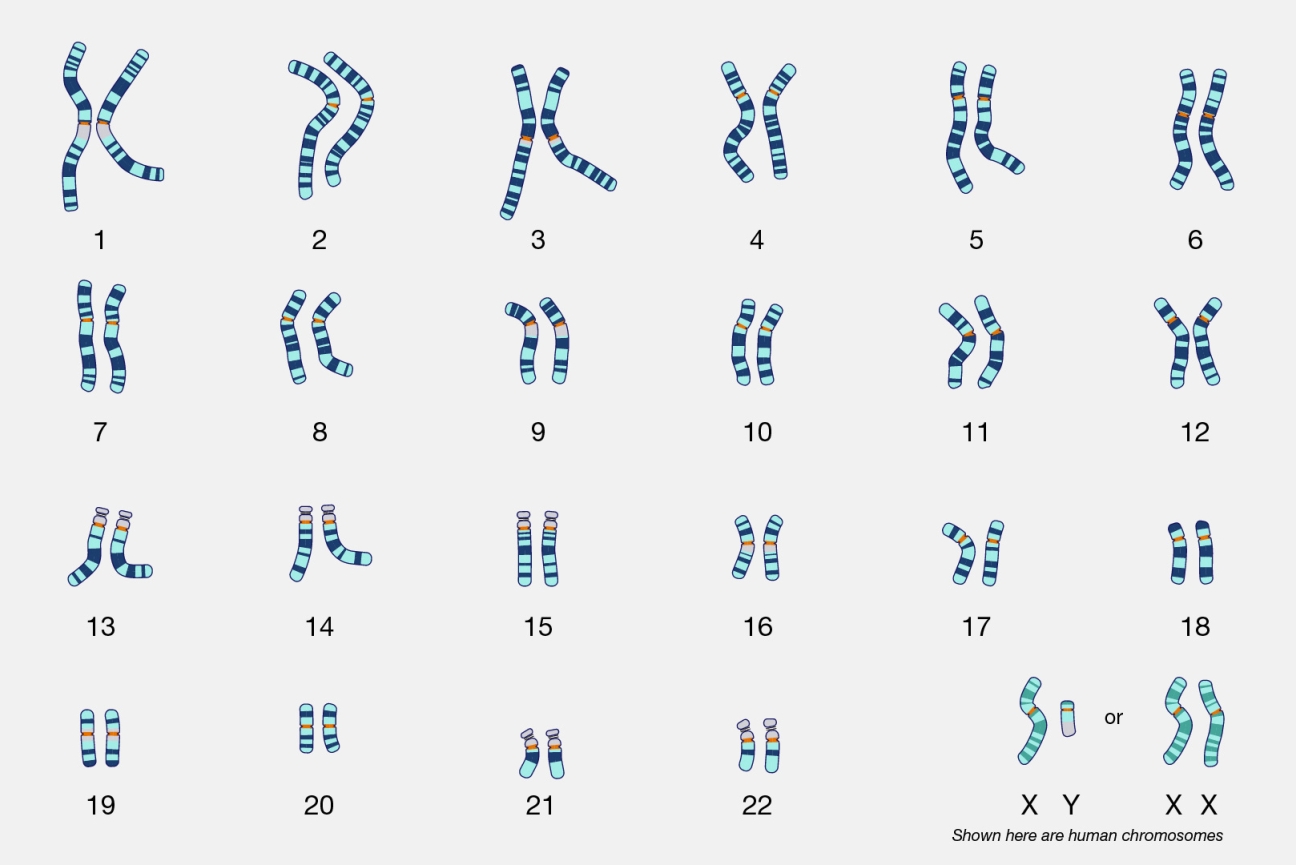

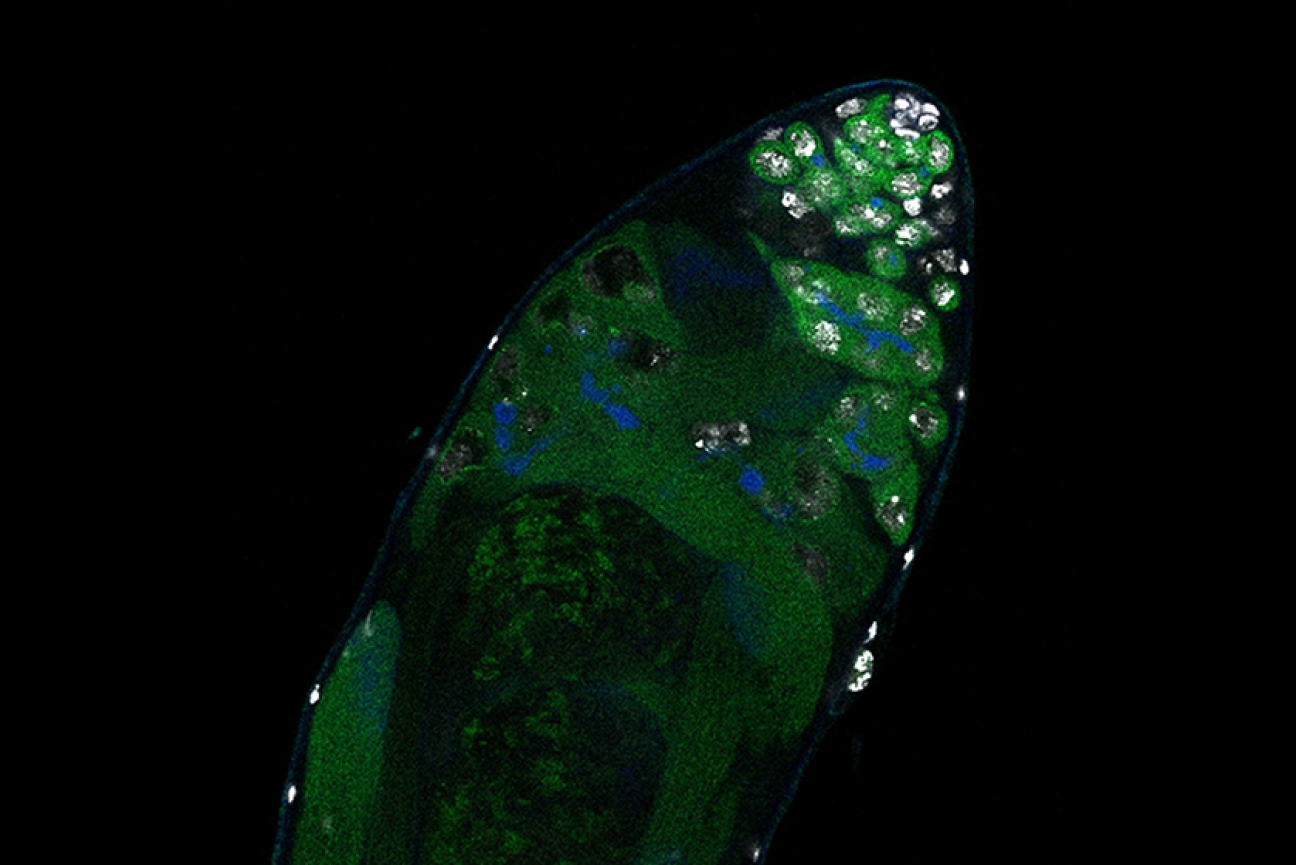

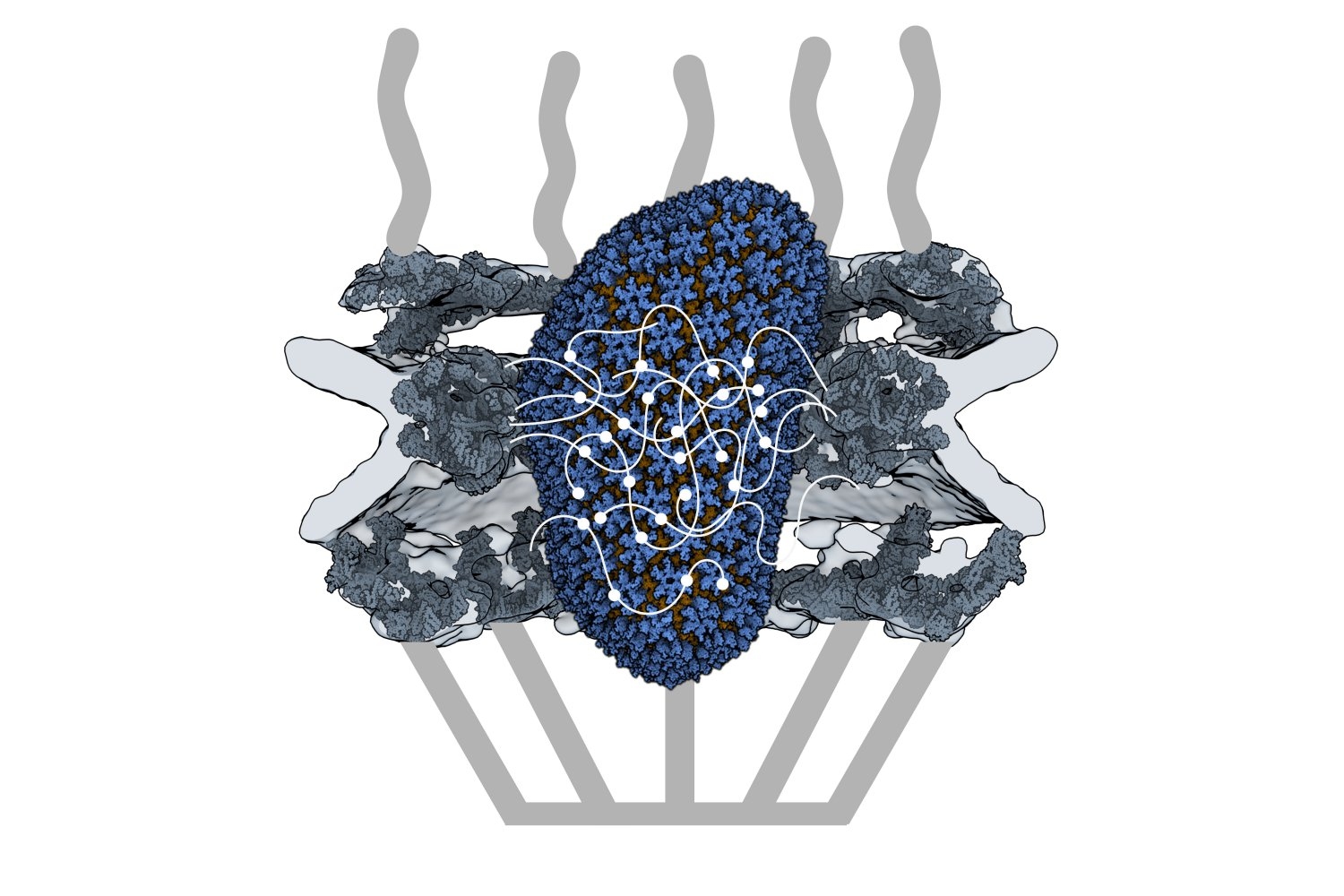

HIV-1 delivers its genome into the nucleus by packaging it into a large, cone-shaped structure called a capsid — but the exact mechanism has remained elusive for decades. Travel through the nuclear envelope occurs through, and is regulated by, nuclear pores, doughnut-shaped protein assemblies. Human cells have about 2,000 nuclear pores perforating the nuclear envelope. Some earlier evidence suggested that the capsid remains intact during its delivery into the nucleus — but this created a dimensional conundrum. The cone-shaped HIV-1 capsid is about 120 nanometers long and 60 nm wide — too large, researchers thought, to fit through the opening of the nuclear pore, measured at only 43 nm wide.

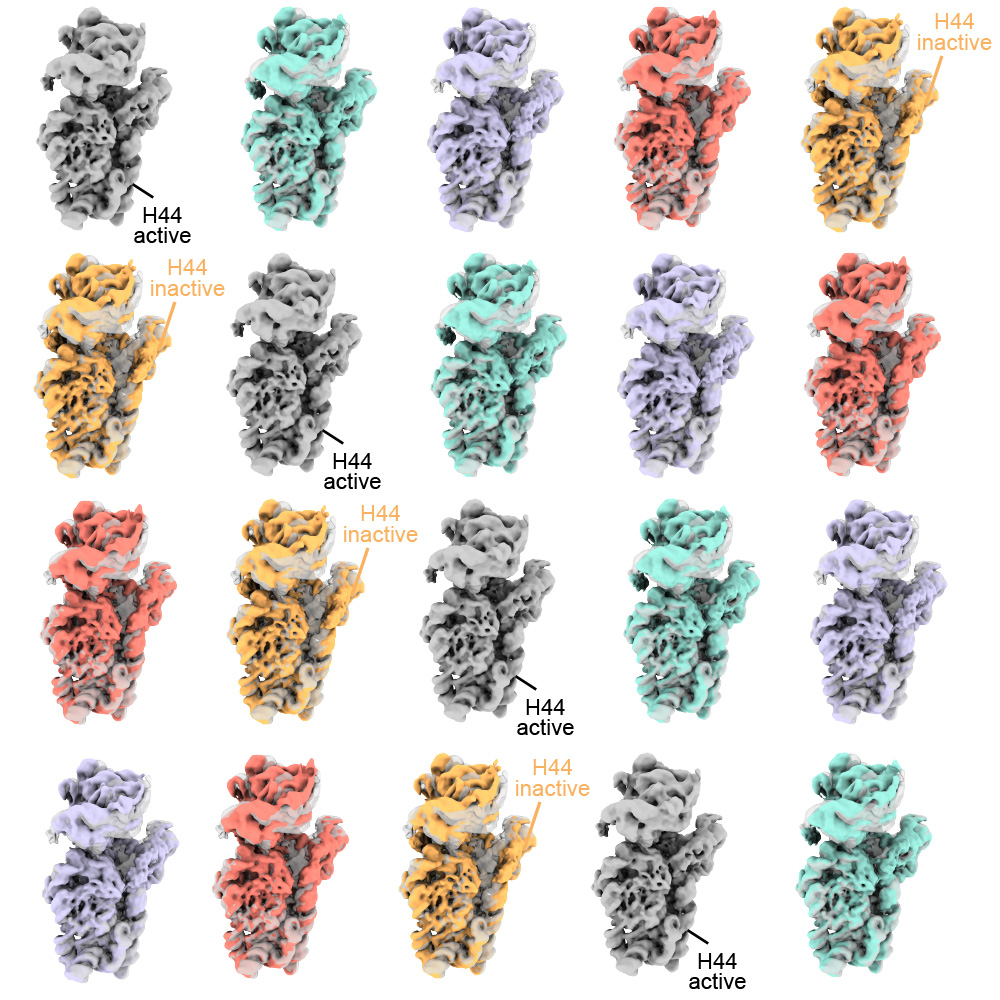

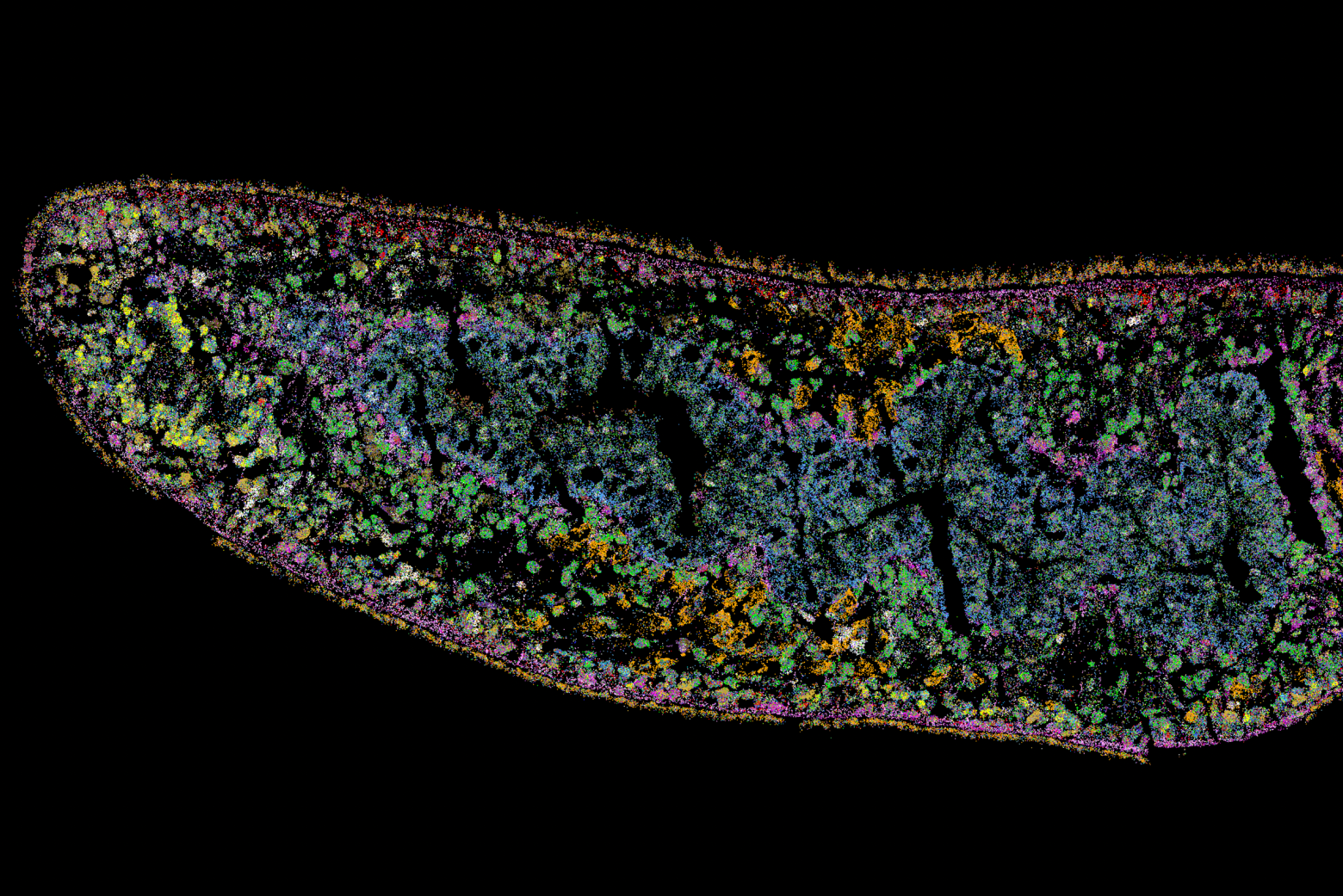

Members of the Schwartz Lab at MIT, in the Department of Biology, became interested in this question when a postdoc in the lab used cryo-electron tomography, slicing up sections of frozen cells to examine structures, to show that nuclear pores in the nuclear envelope are larger than 43nm. They deflate and shrink, it turns out, when removed from their native conditions. In native conditions, the nuclear pore complex is about 60nm wide — wide enough to accommodate the HIV-1 capsid.

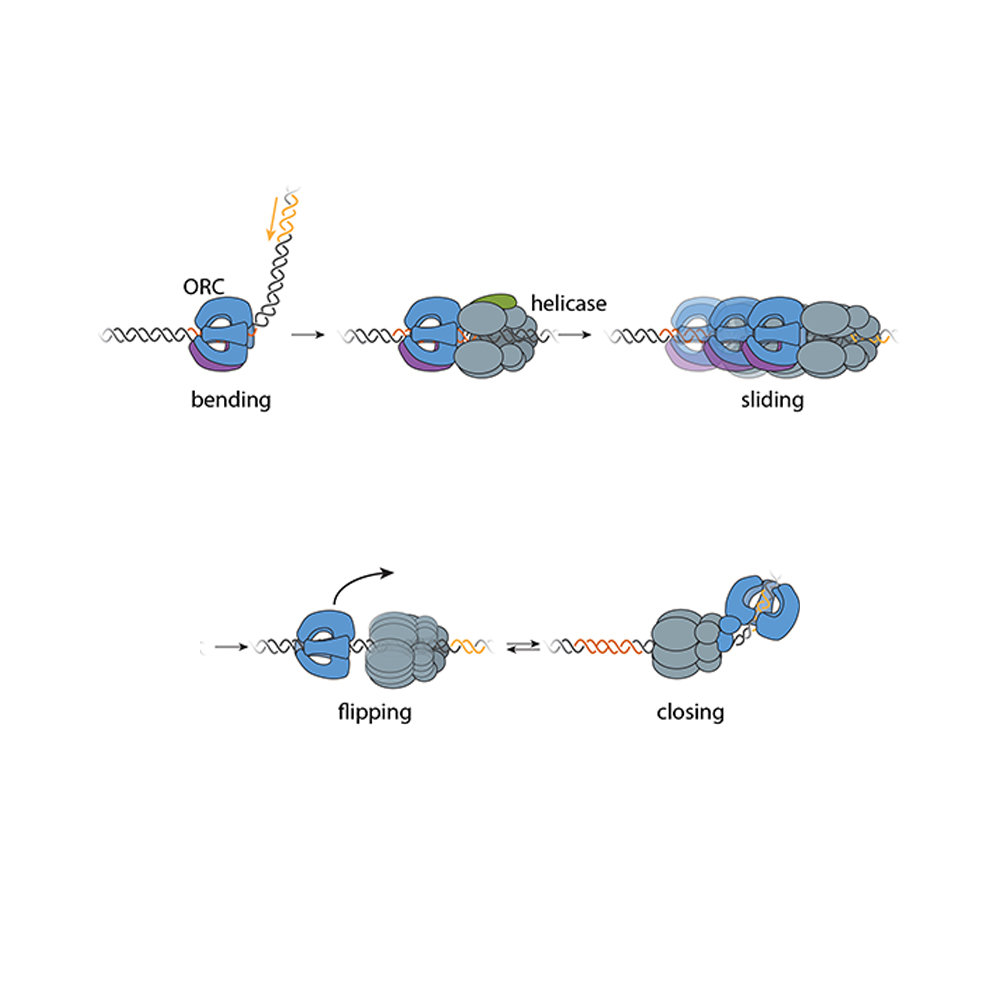

Knowing that it could fit, a question remained: How can the capsid navigate the dense mesh of spaghetti-like proteins that act like a sieve in the nuclear pore channel? That spaghetti-like mesh allows small cargo to diffuse through, but prevents large cargo from entering unless it is escorted by proteins called nuclear transport receptors.

In an open-access paper published today in Nature, researchers present evidence that the HIV-1 capsid mimics the cell’s transport receptors to traverse the nuclear pore.

To support that conclusion, the researchers showed three things in vitro: that an HIV-1 capsid can deliver cargo through a nuclear pore analog; that the capsid can interact with the sieve of proteins in the nuclear pore channel; and that the capsid targets the nuclear pore in the absence of native transport proteins.

Nuclear transport receptors escort large cargo through the nuclear pore by “batting away” the spaghetti-like mesh of proteins inside the channel — like someone holding your hand and guiding you across a crowded dance floor. The HIV-1 capsid interacts with the spaghetti-like proteins, but its purpose is more like a Trojan horse — the capsid encapsulates the viral cargo, protecting it from detection in the cytoplasm and as it enters the nuclear pore complex.

“What’s really amazing about cells is that they are incredibly complex. What’s really difficult about studying cells is that they are incredibly complex,” jokes co-first author Erika Weiskopf, a graduate student in the Schwartz lab. “Biochemists are constantly trying to find ways to study their system in a simplified context, but still give it a flavor of cell biology.”

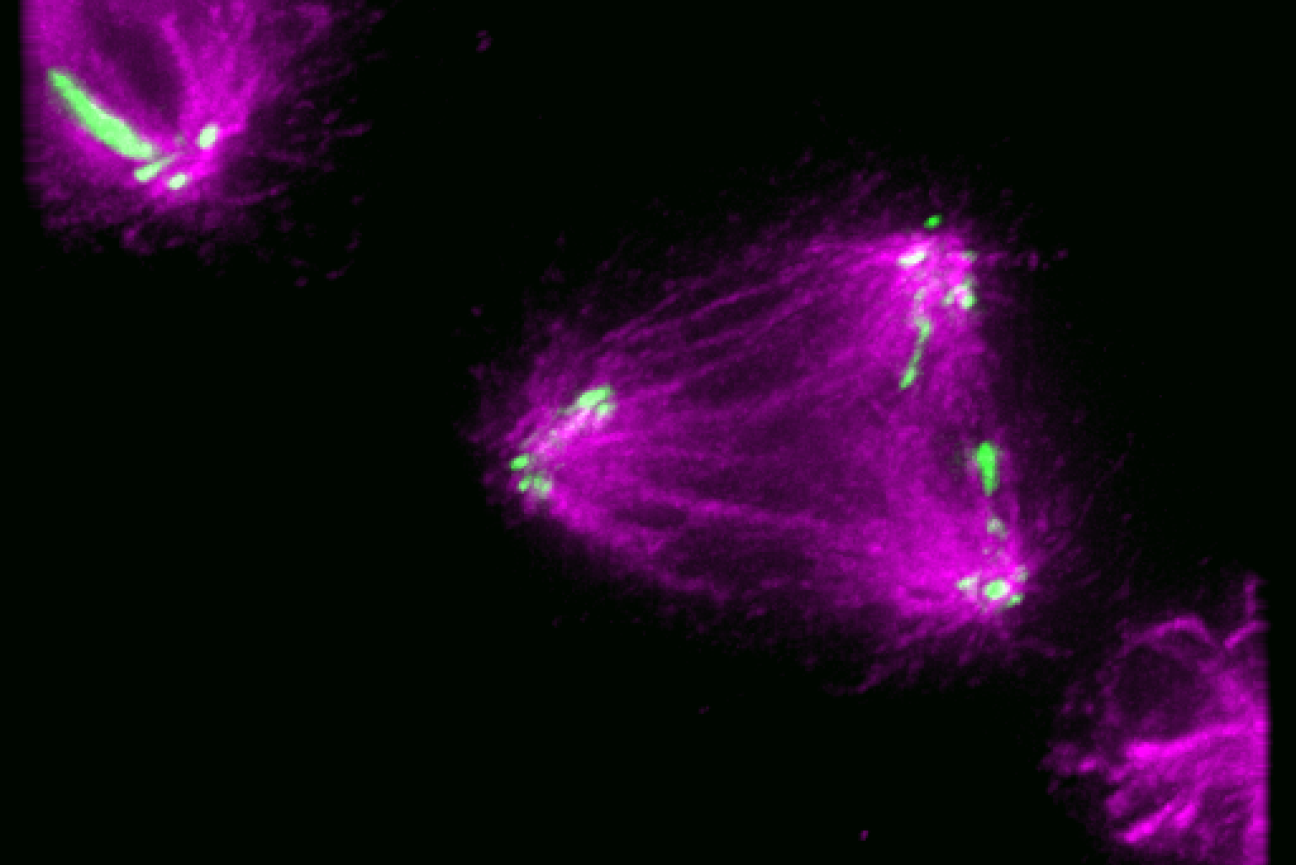

To do that, the Schwartz lab collaborated with Dirk Görlich, the director of cellular logistics at the Max Planck Institute for Multidisciplinary Sciences. Görlich is a co-senior author on the paper with MIT’s Boris Magasanik Professor of Biology Thomas Schwartz. Görlich’s lab has produced concentrated droplets of the spaghetti-like proteins found inside the nuclear pore, and those droplets allow and exclude cargo the same way a nuclear pore will. In experiments, fluorescently-labeled cargo did not enter the droplets, but fluorescently-labeled cargo packaged in an HIV-1 capsid was delivered. This indicated that the capsid could deliver cargo through a nuclear pore.

Using a biophysical binding assay, the researchers also showed that the HIV-1 capsid interacts with the proteins inside the channel. Different spaghetti-like proteins are found in different channel sections, such as at the cytoplasmic side’s entrance or only inside the channel; there are 10 such proteins in human cells. The capsid is a promiscuous binder — it can interact with all the spaghetti-like proteins found in the channel.

The capsid can target the nuclear pore complex even without the cell’s transport receptors, indicating that it is not commandeering native transport receptors to find and enter the nuclear pore. The team used a classic assay in the nucleocytoplasmic transport field to collect this evidence: When cells are treated with digitonin, their membranes become porous. Everything in the cytoplasm will leak out of the cells, but the nuclear envelope will remain intact. Despite the absence of native proteins, the capsid was attracted to the nuclear pore complex, a behavior indicative of a nuclear transport receptor.

Although the capsid behaves like a nuclear transport receptor to penetrate the nuclear pore, it is fundamentally different. A transport receptor doesn’t need to conceal material for delivery the way the capsid does to avoid detection.

These findings open new lines of inquiry for what the nuclear pore complex is capable of accommodating.

“The HIV-1 capsid is one of the largest things that we now know can go through the nuclear pore complex intact,” Weiskopf says. “It raises all kinds of questions — what other things could be going through the pore that we thought was impossible?”

Schwartz said another question is whether all of the 2,000 nuclear pores in human cells are identical or whether there is something that makes certain pores more amenable to allowing the capsid through.

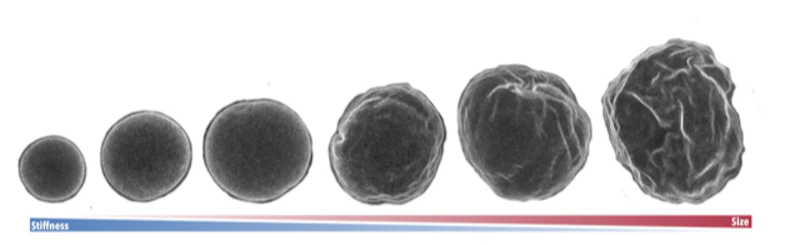

The capsid is also known to be unusually elastic, a property that may be key for passage through the pore. Another interesting question for the field is whether the cone-shaped capsid gains entry into the pore by squeezing through.

Although the team has shown that the capsid can enter the pore, what happens at the other end of the channel is still unknown — whether the capsid fully or partially enters the nucleus or breaks down inside the channel. Weiskopf is working on perturbing parts of the capsid or the spaghetti-like proteins to learn more about which interactions are most important for successful capsid entry.

Although these results have expanded our understanding of the nuclear pore, much remains unknown, both for HIV-1 infection and for the transport process through the nuclear pore complex.

“The nuclear pore is such an important element of cell biology, we thought it would be interesting to understand it better — and that’s how we figured out that the pore is much bigger than we anticipated,” Schwartz says. “We will certainly try to see whether we can understand the mechanism of HIV-1 infection, how the capsid is released on the other side of the channel, and what factors are important there — and to what extent you can manipulate it or influence it for therapeutic applications.”